United Kingdom – 5/24/2021 – By Marco Nannini …

Where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet, the legend of Cape Horn is born

… Cover photo: Marco Nannini “I will never forget Pacific and Atlantic Ocean, I will never forget Cape Horn, I will never forget the albatrosses. I will never forget having lived to see my dream come true, a thought I will cherish that will always be mine, whatever happens to me.”

Cape Horn, Cabo de Hornos, whatever you want to call it, is a mythical place where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet. To the detriment of the name, it is an island part of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago that evokes images of pure and wild nature. Right where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet, our imagination is free and flies. Graceful and elegant, albatrosses brave the storms and winds of the screaming fifties between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Continuous perturbations travelling clockwise around Antarctica push huge bodies of water towards the Drake Strait. Cape Horn and Antarctica create an obligatory passage for wind and sea, exposing all the power of nature.

The very strong howling wind swings at every cold front from North-West to South-West. The winds of the warm sector of the depression blow regularly and very strong for days, raising huge waves. As the cold front passes, conditions become furious. The wind shifts and blows cold, angry, straight from Antarctica, bringing with it waves from a different direction. This is the most dangerous moment, the wave patterns cross and sum up creating a confused, difficult, foolish sea. Many navigators have tasted the icy bites of freeze cold water, the lethal breakers. Where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet, you can experience pure nature, but you can also die.

Note: This article is a translation and we apologise for any errors it may contain.

Forty-two hours to impact – the tension in the air before Cape Horn

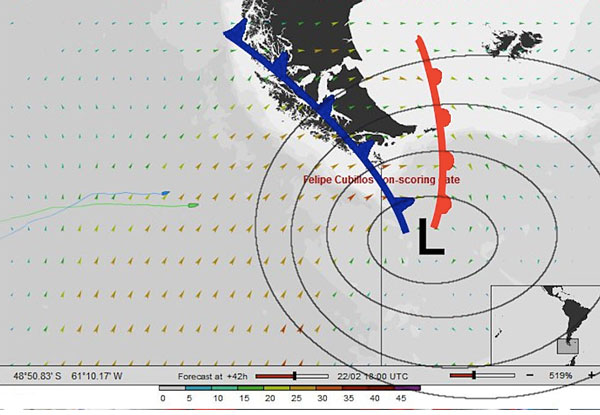

We were sailing 60 degrees south, further south than we would have liked to go, but the weather forced us to do so. I was worried about the drop in the temperature of the water, which was then below four degrees Celsius. It was clear that we were icebergs territory, some had already been reported to us north of us, above 59 degrees of latitude. We were in the warm sector of a very deep depression, a real storm of the type that had fascinated me since I was a child. The depression was reaching us from West to East as we continued our mad flight for Cape Horn. It was February 2012, there were two of us on a racing Class40 during the 2011/2012 Global Ocean Race. Headed to where our dreams had an appointment with the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

At that moment we had temporarily taken the lead of the race, for the first time since the start. Our dive south had paid off but the tension on board continued to rise. With each update of the synoptic chart data, the situation seemed to get worse. We were in contact with the other competitors and the race committee and even the Chilean coast guard had been alerted. We were located 420 miles from Cape Horn, and even with reduced sails in the storm we still held an average of 10 knots. We would arrive to round the cape after about forty-two hours, for our rendezvous between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Cape Horn, where the sea goes crazy, the wind pushes you onto a lee shore

Our analysis, could not ignore an important fact, the dreaded cold front still far away but was pressing on us. As we sailed, the depression and its associated cold front, travelled eastward much faster than us, shortening the distances between us and the cold front. Every three hours with the satellite I downloaded new data but the response was inexorably the same. The cold front would have reached us just about after 42 hours. As cold front would pass, the wind would turn suddenly and violently from North-West to South-West. Right where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet and decide who to let pass.

Our far was multiplied by many worries related to the dangers that we might encounter. Navigation between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans is complicated by many factors. In the warm sector of the depression, the February wind temperature is still tolerable, around ten degrees Celsius. However, with the water around us at less than four degrees and the wind rising above fifty knots, the it was bitterly cold.

In those north westerly winds, we had nothing to worry about in relation to the continent or the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego. In fact, if things deteriorated further, as long as the winds stayed from the North West we could have hove-to or even found some relative shelter from wind and sea closer to shore. This, however only held true before the cold front, when you have free waters to run, if need be, all the way to Antarctica in the passage between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. If the cold front had reached us, we’d suddenly find ourselves in lee shore at the worst possible time.

A matter of hours – the meeting between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans

Everything would have been different if we had arrived where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet with even just a few hours of delay. We would have found ourselves already close to the Chilean cliffs ending up in a very dangerous trap. At the passage of the front a very strong wind from the South West would have arrived, straight towards land. If the conditions had worsened we would have had to try sail away from shore, but without any space to run and to reduce apparent wind. Neither of us onboard had ever faced similar conditions, The wind had been sustained for dozens of hours and the forecast was for a strong deterioration. We did not know what awaited us at the meeting between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

One last aspect disturbed us more than anything else, the orography of the ocean floor just where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet. Where we sailed the sea was majestic, with waves measured by the models between eight and twelve meters high. But their period was very long, as during the whole navigation in the Pacific Ocean. At the tip of a wave you felt like you were on a mountain looking at valleys. On the bottom between two waves one perceived only the insignificant smallness of man in the face of the power of nature. Not far in front of us however, the ocean floor rises from thousands of meters to less than 100 meters near Cape Horn. This sudden rise, just like on the banks of Newfoundland and in the Bay of Biscay, drives the sea state crazy, where the continental shelf begins.

Getting to Cape Horn at the worst time

Everything seemed lined up for us to arrive at the worst possible moment where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet at Cape Horn. We would have arrived at the time of the passage of the cold front, with a crossed sea, wave patters summing up. The waves pushed by the rising currents of the sea from the abysses stand out madly as steep as walls. If we had managed to round the cape before the cold front we could then have headed north during the worst from the southwest. We would have avoided the Strait of Le Maire by going east of Isla de los Estados and heading for the Falklands. We would have pulled out of the fury of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans that meet, protected by Tierra del Fuego and the continent.

Returning to the Atlantic and heading north was all we wanted to do. Finally leave behind us that damned point where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet. But we could not ignore the fact that we were playing on cat and mouse with the passage of the cold front. If the depression accelerated even a little, we could have encountered life-threatening conditions. We adjusted the sails to do our best despite the conditions. Not being able to slow down the pressing depression we could only try to go faster. The wind was picking up, the barometer had plummeted, and everything indicated that the storm would only get worse. It is difficult to imagine that everything can become “much more difficult” when the wind is already blowing regularly above fifty knots.

A difficult decision – the weight of responsibility

We were moving inexorably towards our rendezvous between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. We didn’t talk much, there wasn’t much to say, apprehension was palpable in the air. Neither of us wanted to speak out first and declare their fear. I was sailing with Hugo Ramon, a professional sailor from Palma de Mallorca. Neither had ever seen anything like this, neither could speak from experience. Hugo, in that difficult situation, was extremely correct with respect to his role. He told me that any decision I made he would support without discussion. I was the skipper, the captain, it was up to me to decide, to preserve the first place or to think about safety.

We were quickly reducing the distances from the damned point where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet. Less than a day of navigation to go and the point of no return was given by the decision of whether to step onto the continental shelf or not. Once we “climbed” onto the continental shelf, even if still at sea, our options would be dramatically reduced. We were heading for the Diego Ramirez islands right on our route to Cape Horn. In truth, these small islands represent the outpost of the American continent. They are located right on the edge of the area where the seabed rises, we had to decide before going beyond them.

Continue to win – stop to save yourself

In that leg that would take us between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, two professional teams had already retired. In an agitated satellite phone call with Miranda Merron of Campagne de France, I could hear her confusedly. The sound of the sea was deafening, she just repeated “These boats can’t do it”. This had happened several days before and the most experienced teams, including Ross and Cambell Field turned back for New Zealand the storms we encountered then. Her words echoed in my thoughts, what if we were too late? Were this boats not safe enough for those waters? What if we had arrived between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans right at the crossing of the front? What if the waves crossed and projected onto the shallow water and overwhelmed us? After all, we were sailing on a 12-meter boat that weighed just 4500 kilos. A racing shell that was not indestructible nor invincible.

To sign up for the race we had to demonstrate, in sheltered waters, that in case of overturning we could self-right the boat. In fact, these large and powerful boats remain stable even upside down. In most cases, during an involuntary inversion, you typically dismast. And, in fact, during our simulation we did the test without the mast. The very fact that that test was required to participate made the possibility of an inversion far from remote. From shore race director Josh Hall kept us updated constantly, but avoided making judgements. This is because without being on the boat it is not possible to make an assessment of the situation. Certainly from his words transpired all the worry of those who were following us from home.

A sudden slap before Cape Horn

I still distinctly remember, almost ten years later, when, during the night, the boat was overwhelmed by a breaking wave. The wave came from the South, we could have called it an anomalous wave, but we could see it as the first sign of what we could have faced. The point of no return was approaching but that wave hit us with such violence as to shake the rigging boat and our souls. We were scared, if that was a warning, and it had worked. I called Hugo, I didn’t even have to speak, he knew exactly what I had decided. After a couple of hours it was dawn and with the help of the morning light we went out on deck to get ready to heave-to. A manoeuvre where the boat stops, or at least slows significantly, and remains floating lulled by the immense waves.

The success of that manoeuvre was not to be taken for granted either, racing boats are very light and do not heave-to very well. We had to do several tests before stabilising the boat, but to our surprise everything calmed down. The motion was gentle as we ascended and descended from the huge mountains of the South Pacific. We had hoisted the storm jib and took four reefs, which our mainsail was equipped with. We had two handkerchiefs, but the boat remained stable, she only drifted sideways at two or three knots of speed.

Let the worst pass

The sense of relief at the decision was immense, we found ourselves laughing and patting ourselves on the back. We were tempted to get back on course but we knew that overall that was the right decision. Our direct competitors, with a newer boat, were back in the lead and forty miles ahead of us. Miles that translated into at least four hours of advantage with respect to the passage of the front. They had managed to recover precious time and decided to go straight, counting on rounding the Horn with a little margin ahead of the front and wind shift.

For us, however, the calculations indicated that we would not make it. That rogue wave had only reminded us of the decision that had been weighing in the air for some time. We hove-to for less than twelve hours waiting for the cold front to arrive, as the hours passed the sea got worse and the wind raged. The idea was to resume sailing immediately after the front, in order to arrive where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet with improving conditions. The worst would then be behind us with ample time to go up to the Atlantic before any new depression could endanger us. I.e. go north of Tierra del Fuego before a new depression hit.

Pacific and Atlantic Oceans let us pass

The choice was spot on, at the first signs of the passage of the front we prepared to manoeuvre. As the wind turned from southwest to northwest, we headed back on course towards Cape Horn. Initially the majestic sea was still terrifying, the boat flew in pure uncontrollable surfs with just two tiny sails. The cloud cover was torn, the sun through the clouds on our faces, the sea was slowly realigning itself on the new direction of the wind. The cross sea was fading. Shortly after we passed the islands of Ramirez and although the sea was confused and some breakers hit us we did not fear for the safety of the boat.

Soon we found ourselves shaking of the one reef, at first just one going from 4 reefed main to 3 reef, then we dropped the storm jib and hoisted the staysail. Everything was looking good, with the seabed rapidly rising it crucial that conditions were improving and calming down. It was now not long before we crossed the imaginary line where Pacific and Atlantic oceans meet. We decided to stay way off Cape Horn in deeper waters with less probability of dangerous sea. However, the wind and the sea decreased rapidly and we ended up rounding the cape without even seeing it, under the typical sky of a recently passed cold front.

A few hours later we even hoisted the spinnaker and in the protected waters after the cape we decided to go for the Strait of Le Maire. We had no idea what the currents were doing in those places, we only had a photocopied page of a pilot book. “The Strait of Le Maire is to be avoided at all costs in adverse wind and current conditions”. We had no idea what the current was going to do, we didn’t have the Ushuaia tide tables. We thought then about going outside the Isla del Los Estatos.

One last unforgettable ride

We arrived at the mouth of the Strait of Le Maire in light winds. Behind us we looked towards where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet, we had passed. We were sheltered from the snow-capped mountains (in the height of summer) of Tierra del Fuego. Slowly we noticed that we were accelerating towards the strait, we had arrived right at the change of flow of the current. When we entered the strait the wind was almost gone but the current added three knots to our speed. We were a bit apprehensive not knowing anything about that place and with nautical charts that didn’t seem to have been updated anytime recently. We saw worryingly shallow water on our depth sounder but by now we would not have had the sailing speed even to turn around and go back.

The sea span in vortexes, there were eddies everywhere around us, brown waters that clearly raised from the bottom of the shallow seabed. Contrasting flows created areas with bubbling water and waves rising out of nowhere. We had only about three or four meters of water under the keel with no idea if there were rocks or other dangers. We only knew that the passage was navigable. It looked damn scary and we certainly took stock of the advice in the pilot book, I could not imagine that place in a strong wind against tide situation. The strait soon became a river rushing at speed, we were petrified gritting our teeth and couldn’t do anything but let us be carried forward by the current. The day was drawing to an end and wanted was to get out of that terrifying place. Gradually the strait widened, the fury of the current lessened and pushed us north into a calm sea such as we have not seen in a very long time.

Pacific and Atlantic Oceans greet us

The sun gave us a sunset of infinite calm and peace. We had been where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet, we had rounded Cape Horn and we were finally out of danger. The rest, as they say, is history, even if the rest of the leg was still long and tiring. I will never forget Pacific and Atlantic Ocean, I will never forget Cape Horn, I will never forget the albatrosses. I will never forget having lived to see my dream come true, a thought I will cherish that will always be mine, whatever happens to me.